The Problem

I've had a few chances to build a web application from scratch, but mostly I work on big, old projects with lots of features. Over the years, developers are assigned to a project and other developers leave this project, this causes some parts of the project to become, - I named these parts - "Dark Spots/Areas", things not everyone knows about. I remember working on a project that used ReactJS, but one part was in Elm, which was new to me. This made the project more complex. Changes in one part could affect others in ways we didn't expect. It also meant that not everyone on my team knew about every part of the project.

Because of this problem, companies adopt the microforntend architecture for three main reasons

- Optimize for feature development, A team includes all skills needed to develop a feature from A to Z.

- Make frontend upgrade easier, Each team owns its complete stack from frontend to database. Teams can decide to update or change their front-end technology independently.

- Increase customer focus, Every team ships their features directly to the customer.

What is the Microfontend Architecture

There are two definations for Microfontend architecture

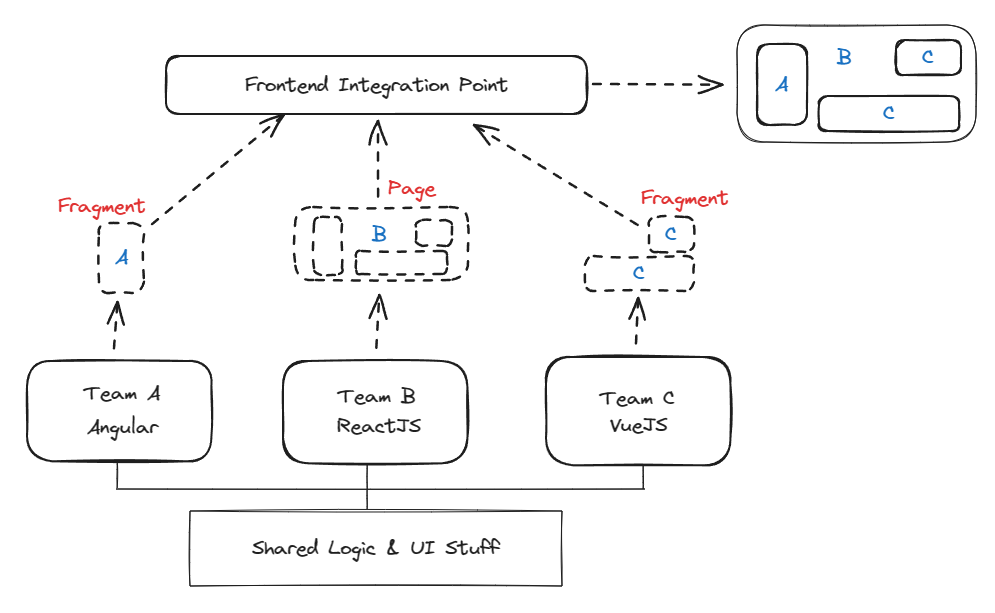

-

An architecture that divides the application into vertical slices. Each slice is built from the database to the user interfaces and run by a dedicated team. The different team frontends integrate into the customer's browser to form a final page. This definition or approach is related to the microservices architecture. But the main difference is that a service also includes its user interface. and this leads to removing the need for a central frontend team.

-

This is my definition - An architecture that divides the application into micro-apps, each app responsible for a punch of features related to one business aspect, each micro-app responsible by the same team or different team, this definition also doesn't care about the backend stack and how they manage their services.

Why Microfrontend?

I am going to share a work-related story, focusing on our decision to completely overhaul an outdated application. Our goal was to develop a new application without being constrained by any specific technology. We aimed for the flexibility to seamlessly integrate Proof of Concepts (POCs), such as innovative ideas that needed rapid demonstration. This required setting up a system that allowed us more control over the application, rather than being restricted or limited by the application itself, especially in terms of feature delivery and technology stack constraints.

One of the key proposals we considered was adopting microfrontends. Initially, this seemed like an excellent idea. However, as time passed, we realized that Micro-Frontends presented certain challenges, particularly in terms of development experience, which became somewhat tedious, and in deployment, where we encountered pipeline complications. We'll delve deeper into these issues later. But the core of our story is our transition to Micro-Frontends to ensure our technology stack was flexible and non-restrictive, allowing us to efficiently manage, deploy, or decommission specific packages as needed.

This was the primary reason for our shift towards microfrontends.

How do we adopt the Microfrontend Architecture?

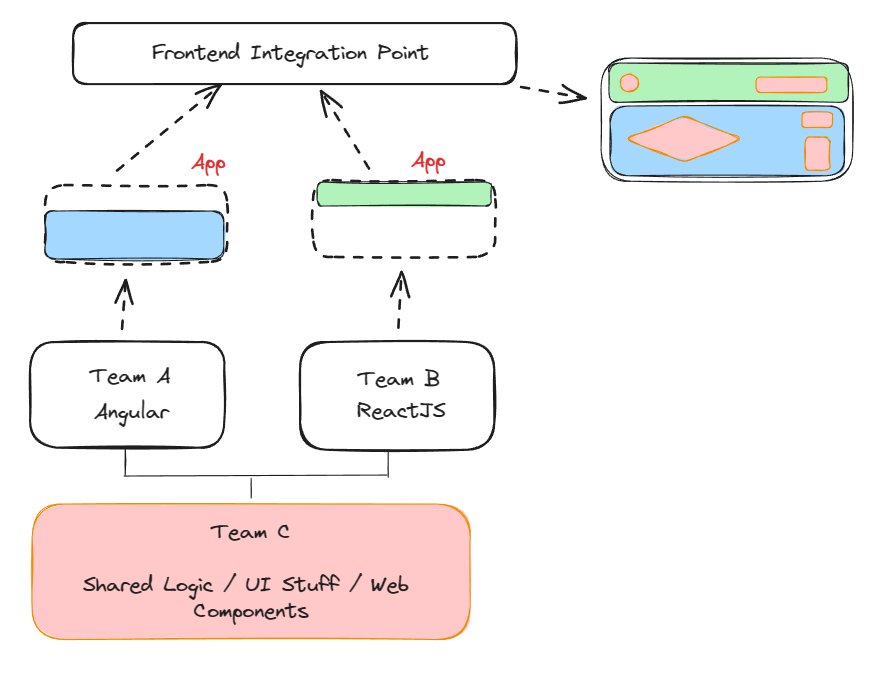

In our microfrontend architecture, we adopted a unique technical approach, diverging from conventional definitions found in textbooks and aligning more with a practical model that I've developed based on my observations in the current project.

Our focus is on the application level, not just components. We've structured the application into what can be described as 'micro-apps'.

For instance, the header of our application is a standalone app. Beneath the header, we have different micro-apps, each aligned with specific business functions. Take, for example, a section dedicated to project management; this is a micro-app encompassing a suite of features pertinent to project management. This segmentation into a distinct micro application allows for focused and efficient management of these features.

Similarly, we have another micro-app tailored to Customer Relationship Management (CRM), incorporating all its features and functionalities. This micro-app, named CRM, is designed to cater to CRM-specific operations.

A key aspect of our architecture is the routing mechanism. The header remains a consistent element across all applications, but based on the navigational route chosen, different micro-apps are loaded. For example, if a user navigates to a route associated with project management, the corresponding project management micro app is loaded. Similarly, navigating to a CRM-related route would trigger the loading of the CRM micro app.

This approach allows for a modular, flexible, and scalable application structure, where each micro-app operates independently yet cohesively within the overall application framework.

Microfrontend Methodologies

In the realm of microfrontends, there are various techniques for implementation, broadly categorized into manual methods and the use of pre-built frameworks.

Let's delve into the manual approach, particularly focusing on Webpack Module Federation (MF).

Webpack Module Federation (MF) is a feature of webpack that allows for the dynamic loading of multiple versions of a module from multiple independent build systems. This allows for the creation of microfrontend-style applications, where multiple systems can share code and be dynamically updated without having to rebuild the entire application.

The implementation of Module Federation in a Micro-Frontend setup typically involves several applications, each with its own distinct entry point. An entry point in this context refers to the initial point of interaction or integration for an application within the larger system. Each of these applications maintains its own Webpack configuration, tailored to its specific needs and functionalities. At the core of this architecture is a central or master entry point. This central point acts as an orchestrator, gathering and managing the loading of these individual applications. This central entry point plays a pivotal role in ensuring that the different applications, each functioning autonomously, seamlessly integrate to form a cohesive and functioning whole.

So, In the landscape of Micro-Frontend architectures, we distinguish between manual methods and framework-based approaches. The manual approach is exemplified by the Webpack Module Federation Example.

Alongside this, there are frameworks gaining traction, such as Single-SPA, and a derivative framework named Qiankun.

Single-SPA

Single-SPA is a well-recognized framework designed for Micro-Frontend development. It facilitates the integration of multiple JavaScript frameworks within a single-page application. Building on this concept is Qiankun, a Chinese-developed framework. It was conceived by a front-end team experienced in using Single-SPA. This team, having identified and addressed specific challenges inherent in Single-SPA, developed Qiankun to streamline and enhance the Micro-Frontend development process.

Qiankun, built atop Single-SPA, offers a refined solution that incorporates improvements and fixes for the issues observed in Single-SPA. Rather than applying individual fixes to each project using Single-SPA, this new framework embeds these solutions, providing a more robust and efficient approach to handling common challenges in Micro-Frontend implementations. Qiankun represents an evolution in the Micro-Frontend framework, integrating lessons learned from Single-SPA to offer a more advanced and seamless development experience.

The Choice

Ultimately, I opted for Single-SPA as our framework of choice. The decision to select Single-SPA was driven by several key factors. Primarily, I sought a ready-made framework that simplifies the initial setup and configuration processes, thereby streamlining the development journey. Additionally, Single-SPA boasts a robust community, offering substantial support and a wealth of resources, which are invaluable for effective problem-solving and knowledge sharing.

The choice came down to two main options: Single-SPA and Webpack Module Federation. While both presented their unique advantages, Single-SPA stood out for its comprehensive framework capabilities and community support. The third potential option, the Qiankun Framework, although promising, was not considered at that time.

Therefore, our selection of Single-SPA was based on its ability to alleviate the complexities of manual setup and configuration, coupled with the strong community backing it offers. This made Single-SPA the most suitable and pragmatic choice for our project requirements.

Gain

Adopting the Micro-Frontend architecture has brought us significant gains, chiefly in terms of flexibility. We are no longer constrained by the limitations typically associated with monolithic applications. The Micro-Frontend structure allows us the freedom to seamlessly add new applications or utilities whenever needed, regardless of whether they are utility-type projects or full-fledged applications. This flexibility extends to both business and technical needs, enabling us to reorganize or relocate modules as required

Another major advantage is our enhanced ability to control routing. With Micro-Frontends, adjusting the routes is no longer a complex or daunting task. This ease of route management significantly reduces potential disruptions and simplifies navigation changes within our applications.

Moreover, our reliance on a specific technology stack, particularly React, has been greatly diminished. While our projects have predominantly been React-based until now, the Micro-Frontend approach provides us the liberty to explore and adopt other frameworks as the project demands. For instance, in situations where React may not be the ideal choice, we have the flexibility to revert to alternatives like jQuery, native JavaScript, or TypeScript. This adaptability is crucial, as it ensures that our projects are not irrevocably tied to a single framework.

This flexibility is particularly beneficial when considering future changes in technology. If the framework we are currently using encounters issues, loses community support, or becomes obsolete, we are not compelled to undertake a complete overhaul of the entire application. Instead, we can continue to use the existing framework for legacy features while adopting a different framework or library for new developments. The Micro-Frontend architecture thus provides us with a tremendous scope to evolve technologically without being hindered by past choices. This capability is invaluable in maintaining the relevance and efficiency of our applications in a rapidly changing technological landscape.

Monorepo?

Before delving into its challenges or irritating features, let's discuss an important point regarding the Single-SPA. Single SPA typically advises that in scenarios where you have a micro-frontend architecture, for instance, segmented into approximately five or six projects — this could include a root project, possibly two utility or parcel projects, and three primary applications (one each in Angular, React, and Vue) — this being your configuration. The principal suggestion is to establish each application within its distinct repository.

Consequently, in line with the concept of micro frontends, it is inherent that each team will be accountable for a separate repository. For instance, if there are five repositories, then there would be a minimum of three teams, with each team being in charge of a main application. One team, for instance, might handle the utilities or helper functions and the root configuration or the primary entry point of the entire micro-application. This rationale underpins the recommendation for each application or individual unit to reside in its own distinct repository.

However, my situation differs. Presently, my setup extends beyond merely segmenting the entire application into several smaller ones. I'm currently managing 11 applications, each representing a single point, inclusive of utilities and helper functions. Among these, there's a UI application comprising custom classes utilized throughout the entire solution, and another dedicated to icons, as we employ custom icons with a unique workflow. Additionally, there are 4 or 5 primary applications, and not to forget, the root configuration application. In total, I am overseeing 11 distinct projects.

A Challenge

Adhering to the Single SPA framework, I'd be compelled to maintain 11 separate repositories, each containing an individual application. This scenario presents considerable challenges and complications, particularly in the context of continuous integration and continuous deployment processes. For instance, introducing a new team member would entail instructing them to clone 11 distinct applications. Consequently, for any given task or feature development, they might need to access multiple applications simultaneously, such as a main application along with two helper applications and icons. This requires either running four instances of Visual Studio or managing one instance with multiple repositories as a combined workspace.

When submitting pull requests, they would need to create four separate PRs, further complicating the management of interdependencies among these PRs. A potential issue arises if one PR is merged ahead of another it depends on, leading to deployment failures due to unresolved dependencies. Managing 11 repositories, each with its issues, becomes increasingly unwieldy, particularly with a small team of three or four members. It’s highly impractical to have the same individual juggling between four or five interconnected projects, potentially running six instances of Visual Studio.

A more logical approach would be to use a single workspace with an instance of VS Code, opening all six projects simultaneously. This would involve managing six terminals, each dedicated to launching an application. Any changes across these six would necessitate individual PRs for each, culminating in six PRs for a single feature implementation.

To circumvent these complexities, I opted for a mono-repository approach. Currently, my setup involves working on a micro frontend using Single SPA, all consolidated under a mono repo. This single repository encompasses all 11 projects and the entire configuration. While this approach introduces its unique challenges and a different set of issues, it streamlines the management process significantly in comparison to handling multiple repositories.

Pain

First, the project naturally had node modules, and the packages themselves became very large. I had 11 projects, and each project had its own node modules folder. Additionally, outside there was another node modules folder for shared dependencies, which are the shared node modules

The node modules have become exceedingly large, occupying 3 to 4 gigabytes just for their directory space. While the entire solution itself might only be around 20 megabytes, the node modules disproportionately swell into gigabytes, presenting a significant issue. Our deployment pipeline managed via Bitbucket, requires a sophisticated setup, which it currently lacks. As it stands, any modification in one project triggers a comprehensive deployment of all 11 applications. Ideally, the pipeline should be intelligent enough to deploy only the affected application, but our current arrangement is inefficient.

This inefficiency stems from our integration within a .NET framework. Our lack of autonomy over version control, and the necessity to conform to certain logic dictated by the .NET shell, particularly for security reasons, restricts us. Consequently, we are compelled to load a single version across all projects. Any frontend change, regardless of its magnitude, necessitates a full deployment cycle.

In practice, this means the pipeline, when executing 11 build commands to generate a distribution folder for each project, takes approximately 15 to 20 minutes to complete a build, even if the change is as minor as a single line in a single file. This situation highlights a broader problem with pipelines in general, where inefficiencies in the setup lead to disproportionately lengthy and resource-intensive processes for relatively minor updates.

Owing to the considerable size of the node modules, we transitioned from npm to pnpm for more effective package management. This switch has yielded significant improvements, particularly in terms of disk space utilization and the efficiency of loading dependencies, as well as the overall handling of the node modules. The approach to package management has evolved; for instance, the initial installation of packages upon cloning the project now requires merely a minute or a minute and a half, a substantial decrease from the 10 to 15 minutes it previously took with npm, a duration contingent on internet speed and the capabilities of the machine. This change to pnpm has markedly transformed our development process.

In a monorepo, where many projects are in one place, you have to be careful with shared things, like dependencies. If two projects use the same dependency, you shouldn't install it in both projects. It's better to install it just once at the root level, the main level of the monorepo. This way, you only have one copy of the package, which makes things simpler and more organized.

Indeed, in a monorepo, it's most efficient to centralize shared configurations at the root level. This includes setups like Prettier, ESLint, and tsconfig, among others. By externalizing these configurations, individual projects within the repository can simply reference them, eliminating the need for duplicating configurations across multiple files. Such centralization not only simplifies management but also ensures that any updates or fixes to a particular configuration are universally applied, thereby maintaining consistency across the entire project.

However, this approach does introduce challenges, particularly in terms of compatibility. Sometimes, a configuration that works seamlessly for one project may not be suitable for another, necessitating the creation of specialized configurations. We've encountered such issues but have successfully resolved them. This highlights a critical aspect of managing a monorepo: the need for constant vigilance and updating of configurations to stay current. Falling behind in updates can lead to complex, time-consuming upgrades later on. Such delays can escalate the difficulty of integrating new configurations, necessitating extensive regression testing and considerable effort to ensure everything functions correctly. Therefore, staying up-to-date is not just preferable, it's essential to the efficient management of a monorepo.

Yes, working with a monorepo means dealing with some tricky parts, like setting up Jest or other testing tools. These tools need to be set up outside of the individual projects but in a way that works for all of them.

One big problem I had was with Storybook, a tool we use. It wasn’t easy to set it up in a monorepo. I ended up making a separate project just for Storybook to manage the MDX files, which are used for documentation. Whenever I need to add or change something in the documentation, I go to this separate Storybook project. I had wanted to keep each piece of documentation with its related component, but that didn’t work out, so I had to keep it separate.

This kind of issue is a downside of using a monorepo. Right now, we're okay because we use React and Storybook is made for React. But if we add a project using a different technology like Angular in the future, I might have to change how Storybook is set up or even start a new project just for Angular documentation. We haven’t had this problem yet, but it could happen.

Development Expereince?

Alright, now that we have a large-scale Micro-Frontend Solution managed by a Monorepo tool, let's discuss the Development Experience (DX) aspect.

When a new team member joins, their initial task is to clone the project. Following this, they proceed to set up the solution by executing 'PNPM Install', which efficiently installs all the essential packages.

The next step for a new team member is to run the solution to confirm it's functioning correctly. However, this is where we encounter a significant issue. In my experience, running the solution on my machine resulted in it consuming over 20GB of RAM, which compelled me to upgrade my laptop's RAM to 32GB. Despite resolving my immediate issue, this solution isn't practical or sustainable for the entire team. It's unreasonable to expect all team members to upgrade their hardware simply to run a front-end project. This is especially true for tasks involving small features that do not necessitate running the entire application. This situation underscores a major challenge in managing resource-intensive development environments. It's unusual for front-end projects to require such a significant amount of resources, highlighting the need for a more efficient approach to handling these technical demands.

Single-SPA Inspector

We have explored various solutions to address this challenge. A primary solution, as recommended by the creators of Single SPA, involves maintaining a continuously published environment. This could be hosted on platforms like AWS, Vercel, Azure, or others. The key is to have a live environment, ideally a development (dev) environment, deployed with the most recent code from the development branch. This environment is distinct from testing, staging, UAT, or production environments.

In this dev environment, Single SPA offers a browser extension called "Single SPA Inspector". Let’s assume our dev environment is already live. If I need to implement a new feature that only requires interaction with one or two apps, I would start by accessing the development environment through its URL (for example, dev.domain.com). Then, I'd install the Single SPA Inspector extension. This tool, upon recognizing that the website is based on Single SPA, displays a table indicating all the loaded packages. In our case, with 11 packages in total, the inspector reveals all 11 packages active on the page.

The remarkable feature of this setup is the ability to override these packages. Let's say, I need to work on a feature involving two applications, running on localhost 4000 and localhost 4001. I can copy these URLs and use the inspector to override specific projects or micro-apps, like the project management app, with these local URLs. These URLs typically end with a JavaScript file (e.g., localhost 4000/organization-name-project-name.js).

Once I refresh the page, the dev site functions normally. Still, now it incorporates the nine packages already deployed along with the two packages that I've overridden with my local versions. As I write any change and hit the save button, they are instantly reflected on the site, thanks to auto-refresh. This creates an experience like running the entire application locally and working on it in real time.

This first method, leveraging the Single SPA Inspector for selective overrides in a live dev environment, is the approach we currently employ.

Docker

The second method involves working without a live dev environment. In this approach, a Docker image containing the entire application, based on the develop branch, is created and hosted locally. You run this Docker container, simulating a live dev environment. While Docker runs in the background, you operate the two specific projects locally, overriding them as previously described with the live dev environment.

Traditional Method

The third method, which was the original point of discussion, entails setting up and running the entire solution on your machine. This includes running all the portals and projects, which is a significant aspect of the developer experience in a learning context or within a monorepo framework.

Final Word

In the end, if I could choose again, I would think carefully about using Microfrontend or not.

If I always worked with just one framework or library, like React, and everyone in the team was good at it from the start, I might just make one big React project. This would be a single, large project. We would pick a way to organize our files, maybe by features, and put all our parts and features in this one project. When the project got very big, we would have to make it run better, like we used to do with old big projects. For example, changing just a little bit in one file could take two minutes to save, because the webpack tool needs to build the project for the page to update quickly. This problem doesn't happen with Microfrontend. With Microfrontend, when I save changes, the page updates fast because the project is split into smaller pieces. But we don't have this problem anyway. We could fix it by using lazy loading and suspense in React. This means if loading a part takes too long and slows down the page update, I would load it only when needed. So, my choice to use Microfrontend or not really depends on how the project starts and how much everyone knows about the framework we are using.

Additionally, I would like to highlight that there is a significant learning curve for any new member joining the project. They must rapidly acclimate to the project's workings, be thoroughly prepared, and grasp essential concepts such as monorepos, Microfrontends, and the development of reusable components applicable at both the application and solution levels. Attention to styling is crucial; indiscriminate customization of styles should be avoided, as they are invariably centralized in a single location. Managing and effectively handling the intricacies associated with Microfrontends is a continuous challenge.

This responsibility frequently falls upon the lead engineer and can be quite burdensome. It necessitates daily communication and alignment with the rest of the team. This includes decisions on whether to implement a feature in a specific project or app, the placement of shared elements, and the approach to documentation. All these aspects demand robust and consistent daily communication and coordination.